Randall

J. Randall Murphy

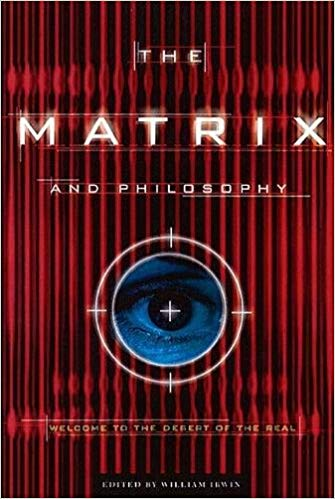

Yes. These fundamentals are all covered in Philosophy of The Matrix. BTW I just watched it again last night for about the 14th time.Jean Baudrillard Simulacra and Simulations ...

NEW! LOWEST RATES EVER -- SUPPORT THE SHOW AND ENJOY THE VERY BEST PREMIUM PARACAST EXPERIENCE! Welcome to The Paracast+, 11 years young! For a low subscription fee, you can download the ad-free version of The Paracast and the exclusive, member-only, After The Paracast bonus podcast, featuring color commentary, exclusive interviews, the continuation of interviews that began on the main episode of The Paracast. We also offer lifetime memberships! Flash! Take advantage of our lowest rates ever! Act now! It's easier than ever to susbcribe! You can sign up right here!

Yes. These fundamentals are all covered in Philosophy of The Matrix. BTW I just watched it again last night for about the 14th time.Jean Baudrillard Simulacra and Simulations ...

Yes. These fundamentals are all covered in Philosophy of The Matrix. BTW I just watched it again last night for about the 14th time.

ndpr.nd.edu

ndpr.nd.edu

Here are a couple of links to short discussions of philosophy in The Matrix:

The Philosophy of The Matrix: From Plato and Descartes, to Eastern Philosophy

Do you take the red pill or the blue pill?www.openculture.com

The Matrix Reloaded | Issue 42 | Philosophy Now

Our movie maestro Thomas Wartenberg plugs himself into The Matrix Reloaded but says that philosophically, it was destined to be dull.philosophynow.org

I've seen one and maybe two of the films but I don't remember many details.

Would you link us to the presentation of the Philosophy of the Matrix? Thanks.

I looked for links on YouTube, but they are fragmented and poorly adapted to YouTube. The thing to do is find a copy of The Ultimate Matrix collection, which includes the clips on DVD or Blu-Ray. It's where I first ran across David Chalmers, a philosopher that @smcder brought to our attention here. I wouldn't however recommend that you get the collection just for the philosophical clips. They are very short and only a companion to the trilogy. A more complete look at the philosophy of The Matrix is:

I looked for links on YouTube, but they are fragmented and poorly adapted to YouTube. The thing to do is find a copy of The Ultimate Matrix collection, which includes the clips on DVD or Blu-Ray. It's where I first ran across David Chalmers, a philosopher that @smcder brought to our attention here. I wouldn't however recommend that you get the collection just for the philosophical clips. They are very short and only a companion to the trilogy. A more complete look at the philosophy of The Matrix is:The shadow of the transcendental: Social cognition in Merleau-Ponty and cognitive science

Shaun Gallagher

Philosophy and Cognitive Sciences

Institute of Simulation and Training

University of Central Florida (USA)

and University of Hertfordshire (UK)

gallaghr@mail.ucf.edu

"'If anything can make plausible Merleau-Ponty’s seemingly paradoxical thesis that human understanding necessarily tends to misunderstand itself, it is, surely, those two particularly rampant forms of logocentric objectivism that today go under the heading of Cognitive Science and Artificial Intelligence.… In their search for the universal algorithm, they represent a kind of innate, genetically programmed disease of the human mind, or, at least, of modernist, Western logocentric consciousness.'

The author of this statement, Gary Madison, was quite familiar with Hubert Dreyfus’s(1972) use of phenomenology in his critique of “good old fashioned artificial intelligence” (GOFAI) -- and of Merleau-Ponty’s role in this. One can see some of the thinking behind this kind of critique in Merleau-Ponty’s Structure of Behavior.

'When one attempts, as I have in The Structure of Behavior, to trace out, on the basis of modern psychology and physiology, the relationships which obtain between the perceiving organism and its milieu one clearly finds that they are not those of an automatic machine which needs an outside agent to set off its pre-established mechanisms” (Merleau-Ponty 1967, 4).

Up until 1991, this had been the only game in town that had anything explicit to say about phenomenology and cognitive science. In 1991 two books changed that. The first, Dennett’s Consciousness Explained, was diametrically opposite to the position that Madison defends, and outlined a quick dismissal of the relevance of phenomenology. The second, however, by Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch, The Embodied Mind, was also diametrically opposite to Madison, but in the opposite direction to Dennett, in showing the relevance of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological notion of embodiment for cognitive science.

Dennett’s book was capitalizing on a new interest in consciousness that was emerging in cognitive science -- ironically, the very idea that motivated phenomenology, but that many “Continental philosophers” were then deconstructing and running away from as fast as possible. In Continental philosophy, phenomenology and the interest in consciousness was in decline at this time, except among a handful of staunch (or reactionary) defenders like Madison, who, in truth (as one might say), were more concerned to react against poststructuralism than to even consider cognitive science. Madison’s pronouncement was not the result of a large analysis, but only a passing comment.

While Dennett was revitalizing GOFAI with injections of neurotransmitters, and placing his bets on distributed brain processes rather than phenomenology, Varela et al. had already bought into Dreyfus’s critique, and were looking beyond the brain to a new incarnation of cognitive science where Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology would find an important place. In 1991, for a perspective that orients itself to Merleau-Ponty, things were not so simple as either Madison or Dennett thought. . . ."

https://www.academia.edu/2826987/Th...nition_in_Merleau-Ponty_and_cognitive_science

This looks quite tasty! I look forward to reading it.

The shadow of the transcendental: Social cognition in Merleau-Ponty and cognitive science

Shaun Gallagher

Philosophy and Cognitive Sciences

Institute of Simulation and Training

University of Central Florida (USA)

and University of Hertfordshire (UK)

gallaghr@mail.ucf.edu

"'If anything can make plausible Merleau-Ponty’s seemingly paradoxical thesis that human understanding necessarily tends to misunderstand itself, it is, surely, those two particularly rampant forms of logocentric objectivism that today go under the heading of Cognitive Science and Artificial Intelligence.… In their search for the universal algorithm, they represent a kind of innate, genetically programmed disease of the human mind, or, at least, of modernist, Western logocentric consciousness.'

The author of this statement, Gary Madison, was quite familiar with Hubert Dreyfus’s(1972) use of phenomenology in his critique of “good old fashioned artificial intelligence” (GOFAI) -- and of Merleau-Ponty’s role in this. One can see some of the thinking behind this kind of critique in Merleau-Ponty’s Structure of Behavior.

'When one attempts, as I have in The Structure of Behavior, to trace out, on the basis of modern psychology and physiology, the relationships which obtain between the perceiving organism and its milieu one clearly finds that they are not those of an automatic machine which needs an outside agent to set off its pre-established mechanisms” (Merleau-Ponty 1967, 4).

Up until 1991, this had been the only game in town that had anything explicit to say about phenomenology and cognitive science. In 1991 two books changed that. The first, Dennett’s Consciousness Explained, was diametrically opposite to the position that Madison defends, and outlined a quick dismissal of the relevance of phenomenology. The second, however, by Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch, The Embodied Mind, was also diametrically opposite to Madison, but in the opposite direction to Dennett, in showing the relevance of Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological notion of embodiment for cognitive science.

Dennett’s book was capitalizing on a new interest in consciousness that was emerging in cognitive science -- ironically, the very idea that motivated phenomenology, but that many “Continental philosophers” were then deconstructing and running away from as fast as possible. In Continental philosophy, phenomenology and the interest in consciousness was in decline at this time, except among a handful of staunch (or reactionary) defenders like Madison, who, in truth (as one might say), were more concerned to react against poststructuralism than to even consider cognitive science. Madison’s pronouncement was not the result of a large analysis, but only a passing comment.

While Dennett was revitalizing GOFAI with injections of neurotransmitters, and placing his bets on distributed brain processes rather than phenomenology, Varela et al. had already bought into Dreyfus’s critique, and were looking beyond the brain to a new incarnation of cognitive science where Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology would find an important place. In 1991, for a perspective that orients itself to Merleau-Ponty, things were not so simple as either Madison or Dennett thought. . . ."

https://www.academia.edu/2826987/Th...nition_in_Merleau-Ponty_and_cognitive_science

@smcder @ConstanceI offer the following just as an example of how wide open the field of consciousness studies is:

Is your ‘true self’ a kind of ghost?

Unthinkable: One of philosophy’s great debates may be down to a misunderstandingwww.irishtimes.com

“Rather sensationally, Trinity College Dublinprofessor emeritus David Berman believes the centuries-old debate between dualists (who believe mind and body are separate) and monists (who believe only one type of stuff exists) is based on a misunderstanding.”

@smcder @Constance

What do you think of the author’s premise? That monism/dualism are natural kinds?

It’s interesting. I’m on the fence. I think culture has a greater impact than author acknowledges.

For instance, I never had an “I exist” moment that I recall, but I was raised in a fundamentalist Christian household. I was taught from a young age that I had a soul and was created by god, was a unique being, no one else like me, would live forever in heaven or hell, etc. I never had a chance to have the “I exist” moment bc it was given to me.

I do agree with the author that we can’t assume all minds are alike. But something else which we may have already covered is how seemingly normal people can hold very extreme views.

Many people are naive realists and this can really effect their thinking about the nature of consciousness. Some don’t even think of phenomenal consciousness when they refer to consciousness. They may just mean self-awareness.

I did have two aha kind of moments which are worth mentioning here:

One day at school, I had this kind of meta social awareness about me and my classmates. It was after a holiday break and we were all entering the school and going to home rooms. And it was like “here we all are doing what we do.” It made me smile for some reason. And I recall literally kicking one of my classmates in the butt, and he was not amused. I guess it was kind of like I stepped back from the herd and observed our collective behavior objectively for a moment, if that makes sense.

Then another time several years, I was at a basketball game in a large gymnasium. I occurred to me how “ludicrous” the b-ball game was with throwing a ball through a hoop, uniforms, rules, etc. I realized that at any minute everyone in attendance could rush the floor and chaos could erupt. Etc. I realized how fragile all the unspoken social contracts we collectively have are or could be. It was a terrifying moment.