We have to look at Lehar's response to Velman. Lehar says it's incredible himself.

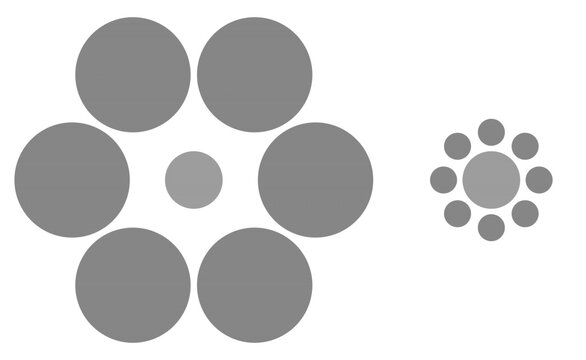

"McLoughlin points out that a volumetric space can be ex- pressed in a sparse, more symbolic code, without recourse to an explicit spatial array, with objects represented as to- kens, with x, y, and z, location, and so forth. There are many aspects of mental function, such as verbal and logical thought, that are clearly experienced in this abstract man- ner. But visual consciousness has an information content, and that content is equal to the information of a volumetric scene in an explicit volumetric representation. Every point in the volume of perceived space is experienced simultane- ously and in parallel. To propose that the representation un- derlying that experience is a sparse symbolic code is to say that the information content of our phenomenal experience is greater than that explicitly expressed in the neurophysio- logical mechanism of our brains.

Velmans’ holographic analogy is very apt. There is in- deed no “picture” as such on a holographic plate, just a fine- grained pattern of interference lines. But for the picture to be experienced by a viewer, or to be available for data ac- cess in an artificial brain, that picture must first be reified out of that pattern of interference lines into an actual im- age again; that is, the holograph must be illuminated by a beam of coherent light. After passing through the holo- graphic plate, that beam of light generates a volumetric ar- ray of patterned light, every point of which is determined by the sum of all of the light rays passing through that point, and it is that volumetric pattern of light in space that is ob- served when viewing a hologram.

So if holography is to serve as a metaphor for conscious- ness, the key question is whether the metaphorical holo- gram is illuminated by coherent light to produce a volu- metric spatial pattern of light or whether the hologram in experience is like a holographic plate in the dark. If it is the former, then conscious experience in this metaphor is the pattern of light waves interfering in three-dimensional space.

It is a spatial image that occupies a very specific portion of physical space, and it requires energy to maintain it in that space. This is exactly the kind of mechanism we should be looking for in the brain. If it were the latter, as Velmans suggests, then why would the shape of our expe- rience not be that of the interference patterns etched on the holographic plate, rather than the volumetric image they encode? What magical substance or process in conscious experience performs the volumetric reconstruction that in the real universe requires an actual light beam and some complicated interference process to reconstruct?

If it is a spatial structure that we observe in consciousness, then it is a spatial structure that we must seek out in the brain, not a potentially spatial structure that remains stillborn in a non- spatial form. Otherwise, the spatial image-like nature that is so salient a property of subjective experience must re- main a magical mystical entity forever in principle beyond the reach of science."

>> So it seems that Lehar really does conceive of phenomenal space as existing in physical space, namely inside the skull.

Edmond Wright

Lehar (sect. 2.4) justifiably uses the analogy with the television screen employed by Roy Wood Sellars, Barry Maund, and Virgil C. Aldrich (Sellars 1916, p. 237; Maund 1975, pp. 47–48; Aldrich 1979, p. 37), in that the distinction made between the screen-state (of the phosphor cells) and what is judged to be shown upon it is structurally similar to that between the sensory evidence within the brain and the percepts chosen from it. If he accepts the co- gency of this comparison, then he ought to acknowledge that the radically nonconceptual nature of the sensory evidence is implied by this analogy. However much information-theoretic evidence there may be on screen/neural raster, it registers only covariations with light-wave frequencies and intensities at the camera/retina, not any information about recognisable entities and properties (if the TV set was upside down and one had just entered the room where it was, one would be unable to use one’s memories to judge that, say, Ian McKellen as Gandalf was at that moment “visible,” the screen thus revealing its permanently nonconceptual state). So Lehar should accept the criticism made above.

Those anti-qualia philosophers and psychologists who inveigh against the “picture-in-the-head” proposal (e.g., O’Regan & Noë 2002), have always opposed the television analogy. Lehar does not sufficiently defend himself against this attack (sect. 2.3).

As I have pointed out (Wright 1990, pp. 8–11), there cannot literally be pic- tures in the head, for, if colours are neural events, actual pictures are not coloured, and the “picture” in the head is. Nor is an eye re- quired for sensing neural colour, for eyes are equipped to take in uncoloured light-waves, and there are no light-waves in the head. Visual sensing is a direct experience for which eyes would be use- less. Gilbert Ryle’s attempt to maintain that one would have to have another sensation to sense a sensation remains as an argu- ment, as Ayer described it, “very weak” (Ryle 1949/1966, p. 203; Ayer 1957, p. 107).

Once this radically nonconceptual nature of the fields is admitted, its evolutionary value can be brought out, which is precisely what Roy Wood Sellars and Durant Drake – the very philosophers that Lehar calls to his aid – insisted upon (target article, sect. 2.3; Drake 1925; Sellars 1922). Sellars particularly stressed the feed- back nature of the perceptual engagement, which allows for the continual updating of entity selection from the fields (altering spa- tiotemporal boundaries, qualitative criteria, etc.), a claim that ren- ders stances such as Gibson’s which take the object as given (amus- ingly termed “afforded”; Gibson 1977), not so much as “spiritual,” the term favoured by Lehar (sect. 2.3), but as literally superstitious.

>> There are a lot of very interesting, rich replies. A nice way to get an introduction to new approaches.

Hoffman

Abstract: Vision scientists standardly assume that the goal of vision is to recover properties of the external world. Lehar’s “miniature, virtual-real- ity replica of the external world inside our head” (target article, sect. 10) is an example of this assumption.

I propose instead, on evolutionary grounds, that the goal of vision is simply to provide a useful user interface to the external world.

Lehar asserts that “The central message of Gestalt theory is that the primary function of perceptual processing is the generation of a miniature, virtual-reality replica of the external world inside our head, and that the world we see around us is not the real external world but is exactly that miniature internal replica” (target article, sect. 10, last para.). I wish to consider this assertion of indirect re- alism.

Suppose it is true. Then we do not see the real external world, nor do we hear, smell, taste, or in any other way perceive it. In- stead, we perceive just the miniature virtual-reality (henceforth, mini VR) that we generate. Given this, what empirical grounds might we have for claiming that our mini VR replicates the exter- nal world? Perhaps we could compare objective measures of the external world against psychophysical measures of the mini VR. If mismatches are minor, we would have grounds for the replica claim. This process seems straightforward enough. The basic sci- ences measure the external world, and psychology the mini VR. So we simply compare data.

But this is too fast. It is not just psychologists who perceive only their mini VRs; all scientists, regardless of discipline, perceive only their mini VRs. So how do the basic scientists manage to measure the external world?

The trouble is that every time scientists try to measure the ex- ternal world, whether they look through telescopes or micro- scopes, they see only their mini VRs. They extend their senses with countless technologies, but the technologies and their outputs are still confined to the mini VRs; for if they were not, then, accord- ing to indirect realism, the scientists could not perceive them. Hence, all scientists are confined to perceive only their mini VRs. If they wish to make assertions about the external world, even as- sertions that an external world exists, then these are necessarily, according to indirect realism, theoretical assertions. They are not direct measures. As Einstein notes, “physics treats directly only of sense experiences and of the ‘understanding’ of their connection. But even the concept of the ‘real external world’ of everyday think- ing rests exclusively on sense impressions” (Einstein 1950, p. 17).

So indirect realism does not allow us incontrovertible empirical grounds to assert that our mini VRs replicate the external world. At best, it allows us to postulate an external world as a theoretical construct. Once we take the external world as a theoretical con- struct, then we have many options for the particular form of that construct. We can, as Lehar suggests, propose that our mini VRs are replicas of the external world.

This is a particularly simple the- ory and, on the face of it, quite unlikely. Our best evidence sug- gests that mini VRs vary dramatically across species (Cronly- Dillon & Gregory 1991), and there are no evolutionary grounds to suppose that our species happens to be the lucky one that got it right. To assert otherwise would be anthropocentric recidivism.

Once we extend our gaze beyond the replica theory, many other possibilities arise. One class of possibilities is that there is little or no resemblance whatsoever between the external world and our mini VRs, but that instead our mini VRs are simply useful user in- terfaces to the external world, with no more need to resemble that world than a Windows interface needs to resemble the diodes, re- sistors, and software of a computer. Of course, we could not call a theory from this class an “indirect realist” theory because, by hy- pothesis, there is no realism.

>> It is the above logic that had caused me to refer to my approach as "intentional" as opposed to "representational."